Since 2015, Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia have set Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) for meeting the Paris Agreement’s goals to reduce carbon emissions and adapt to adverse climate impacts.

However, unresolved tensions between Forest Risk Commodity-driven economic growth and new environmental commitments have led to inconsistent forest management, resulting in significant forest loss.

Southeast Asia is home to 15 per cent of the world’s tropical rainforests, inhabited by around 20 per cent of global plant, animal, and marine species and is where up to 30 per cent of the world’s natural carbon is stored.

Nonetheless, trade-offs between conservation and economic development have put the region’s forests under serious threat.

Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia are central to FRC production – which are goods or raw materials, like timber and palm oil, whose production contributes significantly to forest loss and environmental degradation.

The production and trade of palm oil in Indonesia and Malaysia largely accounts for the countries’ macroeconomic growth and contributes between 85-90 per cent of global palm oil production.

Meanwhile, Singapore is a base of operations for numerous FRC companies, thanks to the country’s strategic role as the region’s financial hub.

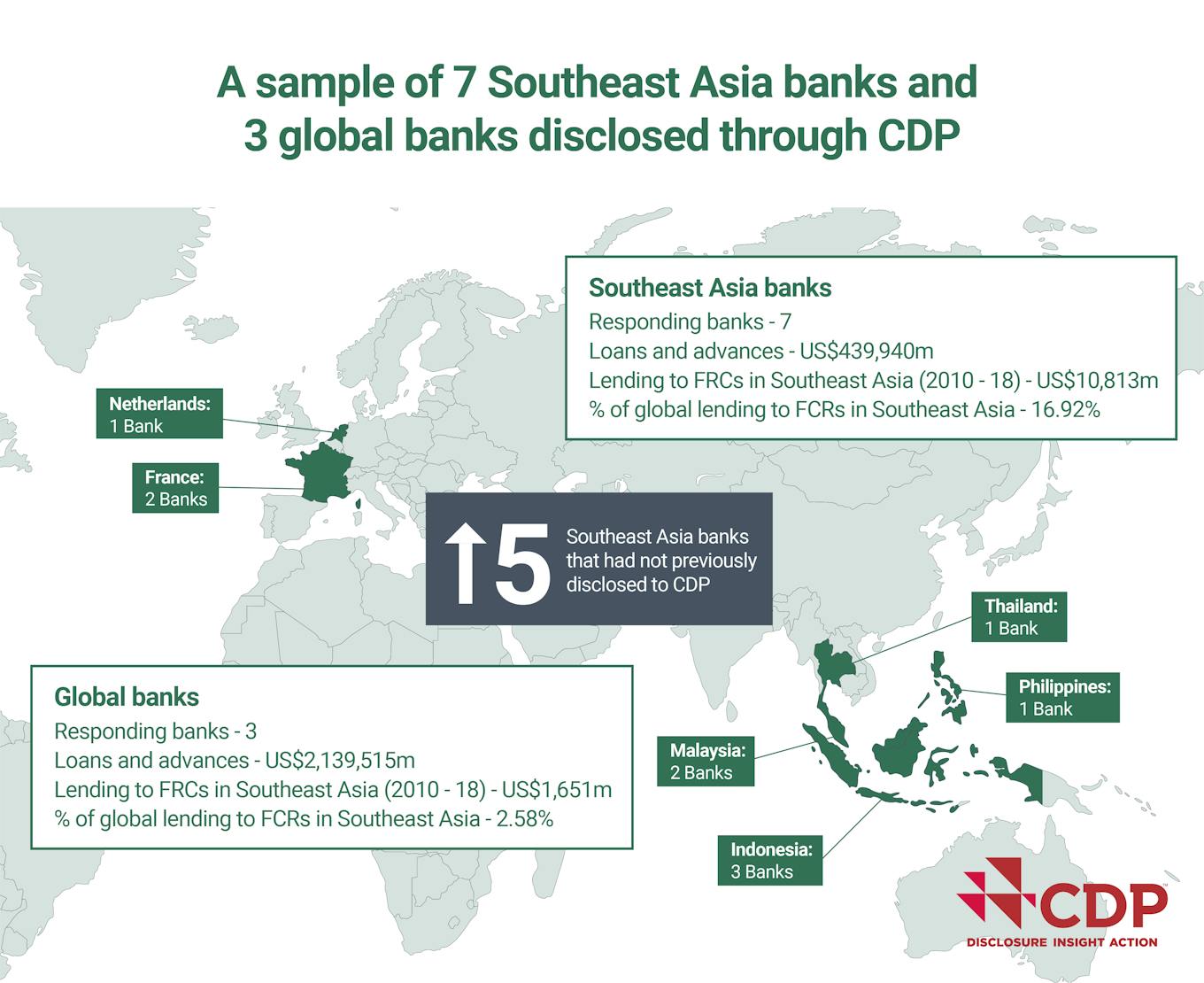

Southeast Asia’s financial sector is uniquely positioned to accelerate changes in environmental action through their lending portfolios given the large volume of capital they supply.

The top 20 Singaporean, Malaysian and Indonesian banks alone represented 37 per cent or US$23 billion of total global lending to the region’s FRC sector between 2011 and 2018.

Risks do not arise from one-off events and will present ongoing threats over the medium-to-long term. Unless more routine and appropriate risk assessment is carried out, the uncertainty over the severity of these impacts will continue to loom large, complicating the actions needed to mitigate the economic, social and environmental consequences.

Policymakers together with banks in the region therefore have the crucial means to address forest and climate risks to accelerate the shift towards sustainable practices within the FRC sector.

As a start, policymakers can strive to better understand and mitigate systemic risks to direct financial institutions on how this can be done.

Measuring the financial risks from climate change and forest loss

As policymakers begin to take stock of these risks an inherent challenge remains, the financial and business implications of climate change, forest loss and land use change may not be immediately clear, easily measured or modelled.

Many risk-modeling approaches deployed by banks are formed on historic trends, which may overlook the evolving nature of forest and climate risk and fail to capture the full-scale impact in their estimates.

To better understand and articulate the relationship between FRC productivity and borrowers’ credit worthiness, we have used a novel approach known as Dynamic Risk Assessment (DRA), which builds on a two-dimensional approach to risk management, constructing a network of risks identified in interviews with experts in FRCs and finance industries.

In the recently published “Forest Commodity Finance: Implications for Southeast Asia’s Policy Makers” policy briefing, we found 19 individual risks relevant to finance and production of FRCs in Southeast Asia. From these, four clusters of risk themes emerge: political scenarios, concentration risk, customer sentiment, and fire risk.

Finance plays a critical role in delivering a forest-positive future. Financial institutions can catalyse change by engaging with the companies they lend to, invest in and insure. Image: CDP

If combined, these risk groups can have substantive impact on the forest commodities industry and the financial sector. Fire risk alone has the potential to affect FRC producers’ revenue by 24 per cent, while the Concentration Risk cluster can reduce revenue by 22 per cent within a period of 33 months.

Risks do not arise from one-off events and will present ongoing threats over the medium-to-long term. Unless more routine and appropriate risk assessment is carried out, the uncertainty over the severity of these impacts will continue to loom large, complicating the actions needed to mitigate the economic, social and environmental consequences.

As both local and international financial institutions invest and lend extensively to the Southeast Asian FRC sector, particularly palm oil, it is critical to address their role in financing deforestation and land use change, as well as how the associated risks affect their portfolios, and potentially the region’s economic stability.

More targeted policies for better forest and climate management

By looking at systemic risks and their scale more closely, more targeted policy actions can be used to de-risk the financial sector through better forest and climate management.

Based on the insights from our analysis, CDP recommends four immediate actions for policymakers and regulators to accelerate the shift towards sustainable practices within the FRC sector.

The first step is to promote comprehensive and transparent forest and climate related disclosures.

This allows for better decision-making, monitoring and assessment of risks. Improved disclosures and due diligence practices offer an opportunity to make better data available to stakeholders and to inform areas for collaboration that will improve environmental performance.

Regulators should consider mandating the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), which provides a well-recognised basis for the disclosure of climate risks.

In addition, the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) has recently released their financial sector guidance and will soon release a supplement to support forest, land and agriculture target setting for the FRC sector and those financing it.

It is also important to ensure forest and climate risks are assessed holistically. Policymakers should analyse the systemic (or network-wide) vulnerability and influence points to fully address the dynamic and interconnected nature of forest and climate change risk.

Understanding which groups of risks are more likely to materialise and how rapidly these risks will pose impact once triggered can help policymakers strategise a clearer course for effective action.

With a deeper, more comprehensive understanding of the systemic risks, policymakers can then implement targeted policy actions to mitigate and prevent the risks from materialising.

To this end, we provide a data dashboard of possible data sources in our Forest Commodity Finance policy brief that can be used to monitor the emergence of individual risks. The indicators may also be useful for tracking the effectiveness of risk-mitigating interventions over time.

We call on policymakers and financial institutions to recognise and mitigate the inherent environmental and social risks that exist within the FRC sector.

Comprehensive disclosures that enable tracking and monitoring business practices will be key to both catalyzing a sustainable practice in the region’s FRC sector and ensuring the region’s long term economic, social and environmental viability.

By Pratima Divgi